CHANGE & DEVELOPMENT IN

iNDUSTRY, AGRICULTURE & tRANSPORT

Some Observations by Noel Walley.

© N.R. Walley, 2001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Industrial Development – Thomas Williams & Co.

Observations on Social Causes & Consequences

Road Transport and Communication

Rail Transport and Communication

North Wales Commuters – The Llandudno and Manchester Club Trains

Summary – Trains from Llandudno Junction (Weekdays) 1947 & 2001

By the same Author:

NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE RAILWAY PASSENGER SERVICES

INDUSTRIAL INFLUENCE ON THE LANDSCAPE IN SNOWDONIA

LLANDUDNO CATHOLIC CHURCH

Author’s Preface

This paper was

inspired by aspects of a ten-week course on "Change and Development in

North Wales” organised by Coleg Harlech

The paper

consists essentially in three essays, one on an aspect of industrial

development in

Noel Walley,

Llandudno, 2001

Industrial Development – Thomas Williams & Co.

Great men are often very complex characters and this seems to be so in Thomas Williams’ case. I found his story quite captivating and it was interesting to contrast the opinion of his workmen who called him ‘Twm Chwarae Teg’ (Tom Fair Play) and that of his business rival Matthew Boulton. It was Boulton who first called Williams the ‘copper king’ – ‘the despotick sovereign of the copper trade’. To his friend and agent he said ‘Let me advise you to be extremely cautious in your dealings with Williams.’ He spoke of Williams as ‘a perfect tyrant and not over tenacious of his word and will screw damned hard when he has got anybody in his vice.’ Of the Cornish producers, Boulton said ‘they would not have submitted to be kicked and piss’d on by me as they have been by them’ (Williams & Wilkinson – partners at one time).

Williams’ tenacity as a lawyer was very evident when acting for the Hugheses of Llysdulas who were in an acrimonious dispute with Sir Nicholas Bayly of Plas Newydd concerning the Parys Copper Mine. This dispute, which ran for over nine years, involved the interpretation of that very unsatisfactory testamentary device called a moiety. At one stage the dispute involved four years of expensive litigation in the Chancery court with the Attorney General and the Solicitor General acting for opposing sides and was not finally settled until 1778. In that year Sir Nicholas leased his own copper mine to a London Banker John Dawes (a secret associate of Williams) for 21 years.

Williams emerged from the

dispute as the managing partner with the Revd Edward Hughes and John Dawes in

the Parys Mine Company. This under Williams control was cheap to run and

extremely productive. His great problem was to obtain an attractive price

for the copper. He faced a cartel of copper smelters whose aim was to buy cheap

and sell dear. He moved decisively to establish his own smelting facilities and

quickly entered into an agreement with John Mackay to establish an industrial

complex at Ravenhead near

He also acted quickly to absorb or control other producers – notably the Cornish mines to produce a complete response to the cartel. Although always the driving force, Williams built up and controlled a major commercial organisation and surrounded himself with able staff. The Revd Edward was always a sleeping partner but younger brother Michael Hughes was an able manager. Other partners and staff included The Earl of Uxbridge, Owen Williams, and Thomas Harrison.

His business organisation was

first rate. He developed the technique of establishing his various businesses

in separate companies. Thus the Parys Mine Company controlled its own smelting

in

The

Thomas Williams of Llanidan

was clearly a complex character; some would say an unscrupulous cheat.

Certainly he was a decisive man who could and did act quickly, as on the

occasion when, without regard for his depositors, he closed the doors to pre-empt

a run on his

The Agrarian Revolution –

Observations on Social Causes & Consequences

– A Personal View

This session raised for me

more problems than it solved. That there was a clear need for reform in

the 18th century was undeniable and the story was well told. What

wasn’t clear was why this should be so and I allowed myself free rein to

consider the matter more fully. There was a significant shortage of food for

labouring people – food is always available for those with money. Thomas

Williams apparently complained that the villagers on

In a different part of

Agriculture was the great

gift to the world of the Mesopotamians and they developed considerable skill in

the efficient sowing of crops – recording some quite remarkable yields. The

Romans introduced to Britain cultivation and husbandry on a large scale and by

good organisation and management (and indeed some early mechanisation) they

were able to secure the very high yields (much higher than subsequently) that

were needed to meet the heavy demands for food and wine of the resident army,

the multitude engaged in metalliferous mining, and both the rural and the

increasingly urbanised native populations of Britain; together with a surplus

for export. In the centuries following the collapse of the Romano-British

civilisation,

Additionally, in the post

Roman era,

This use of the church for population control was fortuitous rather than planned, indeed the churches were and are traditionally opposed to birth control, but down the centuries and from an early date the monasteries were undoubtedly used as population and inheritance regulators [e.g. sons – the first to the family title, second to the church, third to the army, fourth to a trade etc., to prevent fragmentation of estates with consequent loss of power – Welsh traditions, I understand, were rather different – but some Welshmen did become monks for family reasons].

A notable case was that of

the Welsh Henry

The Anglo-Saxon kings had

also been adept at using the monasteries to accommodate and regulate surplus

princesses and royal widows. The traditional Anglo-Saxon Royal monastery

was a double monastery of monks and nuns living in entirely separate houses on

the same site but jointly ruled over by a Royal or a Noble Abbess. The monks

celebrated Mass, studied, wrote and provided the spiritual direction for the

community. For their part the lay brothers would do the heavy work of the

monastery including maintenance of the abbey buildings, labouring on the abbey

farm and managing the extensive outlying estates as well as providing

protection from attack for the monks and also for the nuns. Their duties would

include the production of elaborate needlework for the abbey and the

The suppression of the

religious life during the ecclesiastical reformation under Henry VIII, and

later, under Edward VI, the suppression of the chantry chapels and schools and

the abolition of compulsory celibacy among the clergy, led to a steadily

increasing population especially among clergy families and the ruling classes

who generally expected and therefore secured a far better than average standard

of living. The great monastic and chantry estates, ‘privatised’ by the

government of the day, would be insufficient to support the overburden of

families (children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren) in exponential growth

of those who were no longer given the opportunity of a celibate religious

vocation. The 10,000 parochial clergy of

In the event, population in England & Wales rose from under 4,000,000 at the start of Queen Elizabeth’s reign in 1558 to 5,500,000 at the start of Queen Anne’s reign in 1702 and then rocketed to 9,000,000 by 1801. It is not said that this is the result of the abolition of clerical celibacy, only that the latter was a factor.

It is now recognised in

many church circles that, notwithstanding the spiritual value of self-denial,

the real aim of ‘fasting and abstinence’ was to limit food consumption in order

to conserve food stocks and in particular to ban the eating of meat, including

eggs, in the early spring – when in fact little was available – in order to

preserve the breeding stocks. It is very noticeable that the Friday,

Lenten, and Vigil fasts were not changed in the 16th and 17th

century church reforms and continued to be rigorously enforced by government

decrees during the Elizabethan and Stuart periods. They are all specified in

the tables at the front of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer and amount to about 120 days each year on which the

eating of meat was totally forbidden by law and frugality was encouraged. This

was of course the situation not just in

By the mid 18th century, the old Lenten fasting disciplines had broken down (except in Catholic Countries) resulting in further food shortages amongst the poor. Population was growing rapidly and Agrarian reform, long overdue, was inevitable.

Road Transport and Communication

The value of Thomas Telford’s work in constructing

turnpike roads and especially the A5 to serve

The value of Thomas Telford’s work in constructing

turnpike roads and especially the A5 to serve

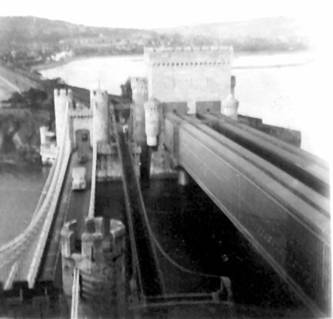

Look carefully!

There is a

Rail Transport and Communication

North

Wales Commuters – The Llandudno and Manchester

Good train services between

the

The service started in the

early years of the 20th century and the London & North Western

Railway and its successor the London Midland & Scottish provided special

saloon cars dedicated to the use of first class season ticket holders. The

saloons were serviced by an attendant who would ensure that a member’s

favourite armchair was kept free for that individual’s use. Members enjoyed the

benefits of newspapers and light refreshments en route to and from

The train started from

Llandudno at

These express services,

which were also available to third class passengers, did much to establish the

Today

The Beeching Era.

In 1961, Sir Harold Macmillan – ‘Mac the knife’ – announced in Parliament:

First the industry must be of a size and pattern suited to modern conditions and prospects.

In particular, the railway system must be remodelled to meet current needs,

and the modernisation plan adapted to this new shape.

Thus it was that Dr. Richard Beeching was appointed Chairman of British Railways in 1961 with very clear terms of reference, and within two years the Board published his report The Reshaping of British Railways, which was remarkable in many ways and not least for its shortness. This report was only 60 pages long but with 88 pages of appendices (tables of unidentified traffic studies etc. and long lists of lines, stations, passenger and freight services recommended for closure or for some unspecified ‘modification of services’) together with a supplementary volume of very inadequate maps on which very few stations were named or even shown. In his book Out of Steam Robert Adley MP commented thus:

For a task of such importance, not just for the Railways but for the nation, one can be excused perhaps for being surprised at the document’s brevity. In a mere 60 pages is analysed the existing state and future prospects of the passenger, freight and parcels services of the railways, and from that analysis were drawn conclusions, the implementation of which has had and still does have a fundamental effect on public transport in Britain.

In some ways the Beeching report and Dr. Beeching’s very short chairmanship (less than four years ending in May 1965) were valuable in that they forced the railways to improve efficiency and to concentrate their resources where they could most effectively generate income. Also, and this may seem surprising given all that has been said about him, it is recognised that during his period in office there was a significant improvement in morale (attributable largely to Beeching’s personality and management techniques) amongst railwaymen at all levels and especially in the upper managerial levels and that despite some resentment at the influx of experts from outside the industry (views largely expressed by Robert Adley). But note also the report to Parliament was 65 pages long. Most Parliamentary reports, before and since, spend the first 100 pages on the preamble. Parliament acted on that insult as the writer proposed, yet failed to learn from his brevity and his managerial skills. Yet the railway system did.

My original home was in

Crewe, and I can identify with the above from personal experience, having

worked for British Railways ten years, (apart from two years in the RAF), until

I moved in 1959 to Stoke-on-Trent Corporation. Morale was indeed at a very low

ebb in the late 1950’s, when Senior accounting men at Crewe still bemoaned the

LNWR’s takeover by the Midland in 1923 to form the

Dedicated railway operators have always run the railways with great professionalism and since nationalisation massive strides have been made to upgrade and improve the railway service. Much damage was done, however, following Beeching because changes of a fundamental and irreversible nature were made to the railway network and the railway infrastructure for relatively small short-term financial considerations. Many of the closures made under Beeching, especially of lines which appeared to be lightly used duplications of other routes, are now regretted, not least because valuable linear rights of way have been lost in piecemeal disposal of railway land.

However, with the dead wood dramatically cut away, the trunk lines were able to concentrate on that which they do best – fast and frequent ‘Intercity’ services (an entirely British concept of c1970 – later imitated throughout the world, and even to the extent of copying the name) between railheads and major centres of population, commerce and industry.

Everyone knows of Dr Beeching yet few would be able to name Sir Peter Parker, Chairman from 1976 to 1983, who recognised the social importance of the railway network and the obligations arising there from. He was an energetic chairman and a persuasive advocate of railways and did much to ensure continued public financing of those railway services that were deemed to be socially necessary. In retirement, he is an official Patron of the Ffestiniog Railway Company (one of six named by the company).

Welsh lines that owe their

survival to Sir Peter’s social railway policy include the

The following table illustrates some of the very great improvements made in the North Wales Coast passenger train services arising from the ‘Social Railway Policy’ promoted by Sir Peter Parker and largely resulting from his proposals, but with continuing improvements over the years. About three quarters of the trains operating these passenger services have been replaced within the last five years by fast modern air-conditioned trains in a massive ongoing investment programme.

Summary – Trains from Llandudno Junction (Weekdays) 1947 & 2001

Train times have been obtained from published winter timetables for 1947 and 2001.

1947

was the last year of operation by the

The numbers of through trains are shown together with the best journey time available.

Further study would show that the passenger service in 1947 was very similar to that of 1939 or 1924 or indeed 1910. There were very few improvements during the 1st half of the 20th century; since steam operated railways had by 1910 effectively reached the limits of economic development.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

October 2001 - Through

Trains - Llandudno Junction to

Llandudno Junction

depart:

Manchester Piccadilly depart:

Almost all trains normally take less than two hours.

NOTES & REFERENCES

J. R. Harris, The Copper King: A biography of Thomas Williams of Llanidan (Liverpool University Press, 1964).

J. R. Harris, The Copper King: A biography of Thomas Williams of Llanidan (Liverpool University Press, 1964).

Several web sites were useful including http://www.angleseymining.co.uk/ParysMountain/AHT.htm which is the official Amlwch Industrial Heritage Trust site, and http://www.rhosybolbach.freeserve.co.uk/ being the site of the Parys Mountain Underground Group, which is dedicated to the archaeology of the site.

J. R. Harris, The Copper King: A biography of Thomas Williams of Llanidan (Liverpool University Press, 1964).

Some Welshmen did become monks for family reasons – a good example of this was our very own Saint Tudno about whom Margaret Williams & T. F. Wynne tell us that Tudno was one of the seven sons of king Seithenyn whose legendary kingdom in Cardigan Bay was submerged by tidal activity. Each son in reparation for his father's neglect (so it was seen – for ‘Seithenyn and his court had given themselves up to eating and drinking, and that greater wickedness – insolent pride of heart’) studied in St. Dunawd's college at Bangor Iscoed. Four sons became monks and missionary hermits.

G. M. Trevelyan, O.M., English Social History (London, Longmans, Green & Co., 1942 & 1955) Ch XI page 341.

The Book of Common Prayer according to the Use of The Church of England (London, Eyre and Spottiswoode Ltd) A Table of the Vigils, Fasts, and Days of Abstinence to be observed in the year.

G.

M. Trevelyan, O.M., English Social History (London, Longmans, Green

& Co., 1942 & 1955) Ch

Henry

Rees Davies, A Review of the Records of The

Robert Adley, Out of Steam: The Beeching years in hindsight (Wellingborough, Northants: Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1990), page 34. [Quotation from Hansard]

British Railways Board, The Reshaping of British Railways - Part 1: Report and Part 2: Maps (London: H.M.S.O., 1963).

Robert Adley, Out of Steam: The Beeching years in hindsight (Wellingborough, Northants: Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1990), page 34.

First

North Western Trains

Email: Author or Webmaster

By the same Author:

NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE RAILWAY PASSENGER SERVICES

INDUSTRIAL INFLUENCE ON THE LANDSCAPE IN SNOWDONIA

LLANDUDNO Queen of welsh resorts

Links Updated August 2005